On Football, Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction, and Freedom

Before Andre Hardy was a writer he was an athlete, and a damn good one at that. He was strong, fast, coordinated, powerful—the kind of talent you don’t deny. Choosing to embrace his talents, Andre trained hard, worked hard, and believed in himself—hard. He developed quickly. He started playing football his junior year of high school, the odd-shaped ball still awkward in his hands, but in just two years he was holding the ball firmly, the two running their way to a football scholarship at St. Mary’s, a Division II school. Three years later, Andre was the 116th pick in the NFL Draft by the Philadelphia Eagles.

“If you’re serious about it, which I was, the athletic journey requires everything you’ve got, to the point you don’t have time for anything other than: eat, drink, train,” Andre says. “I have that compulsive gene where I am always trying to figure out ways to get better and I just let it take over.”

But after just three years in the NFL, Andre broke his foot and never fully recovered. The end of his athletic career was jarring, leaving Andre reeling to find a new sense of purpose. And so, Andre, always a reader, turned to the written word, trading in playbooks for piles of detective fiction and self-help books. He took off his helmet to get better acquainted with what was inside his head, trading in the football for a pen.

His journey began with several screenplays written off as “too literary,” and then stumbled along with six years worth of stubborn draft manuscripts wrung to death in writing classes. Finally, and with financial support from The NFL Players Trust and The NFL Player Care Foundation, Andre signed up to get his MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University, focusing on hard-boiled detective stories. Although his athletic career was a distant memory, his body was still full of the aches and pains that, although insufferable, paved the way for his life as a writer of his beloved hard-boiled detective fiction.

The open-endedness of Antioch allowed Andre to dedicate himself fully to everything hard-boiled. In just two years, he became a scholar who, like a mad genius, departs on expert tangents about the language cannon of pulp fiction or the innovation in the literary craft of Dashiell Hammett.

Taking cues from Hammett’s revolutionary ways, Andre aspires to likewise innovate the conventions of the form in his first book, Allegory of a Cage. He keeps some crucial traditions, like describing characters by their cigarette of choice and lighting scenes with sodium street lamps. But in telling this story Andre feels he has to write, he breaks with the genre’s rules in specific and important ways.

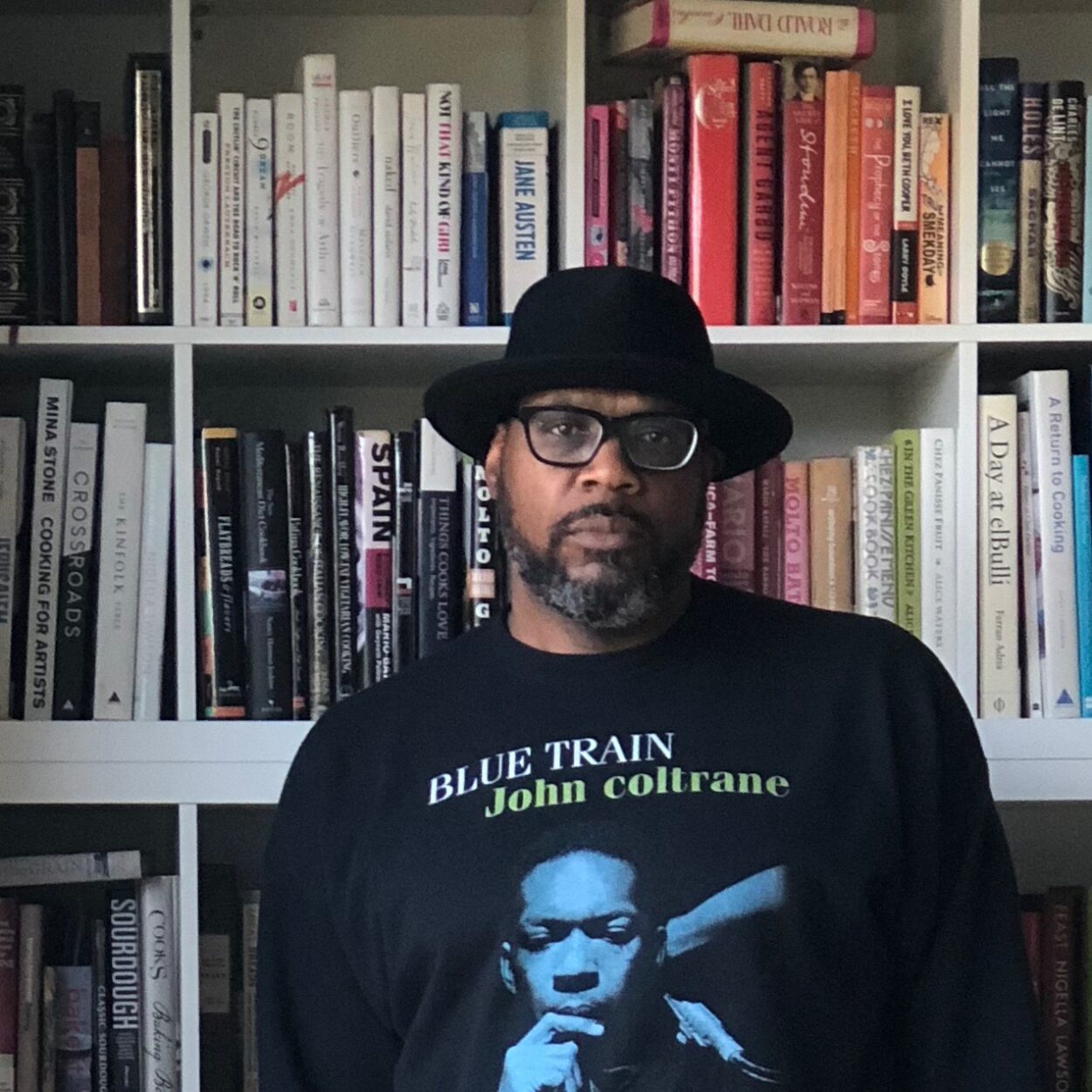

For one, his lead character, Coltrane, is not poor, as are most detectives of the page. For another, Coltrane wasn’t trained to be a fixer by the military or police, like most detectives of lore. Rather he was prepared and toughened by the streets. But the biggest divergence is found in point of view.

“The biggest break from convention is the story being told through a black character, one who recognizes whiteness,” Andre says. “He sees it and he gets it and he comments on it throughout the story.

Coltrane offers “an astute observation about the African American experience that aspires to actually cross the line and enter into that world, by which I mean the white world. Our goal is assimilation—to have brand names and to move out of the hood and into ‘that’ world. But what Coltrane is figuring out is that that’s not really it… there’s gotta be something else.”

Which is to say that writing Allegory of a Cage was as much a literary expedition as it was a personal one for Andre, the making of the book hovering somewhere in between his life and that of the fictional Coltrane’s. Andre’s not shy about imbuing his character with his own experiences and insights, explaining that Coltrane’s suspicions of the white world are vital for the author too, who often feels unseen—an invisibility which is its own kind of cage.

But, in recognizing that he was not as free as he thought he was, Andre, alongside his characters, finds the opportunity to consider ‘freedom’ head on. In asking “what would freedom be,” he and Coltrane are finding it together, one step at a time.